The paper is a speech delivered by Senyo K. Hosi in October 2018 at the Africa Development and Investment Convention (ADIC 2018) in Zurich, Switzerland. The paper interrogates the ‘Africa rising’ phrase and explores whether Africa is rising with its people. It assesses challenges Africa faces with its sustainable development and proposes a way forward with a view on how politics, industry and economic partners should be positioned.

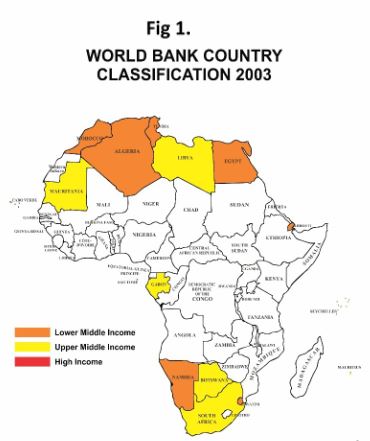

The map of middle- and upper-income countries in Africa looked like this in 2003 (15 years ago). Fig 1.

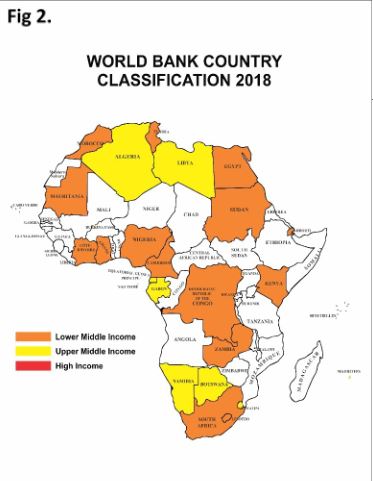

Today it looks like this (Fig 2)

These images are quite telling in the Africa Rising narrative which has become quite a common and attractive phrase, used by analysts and politicians alike. This change in the income status of African countries has legitimised the reference to them as African lions (analogous to Asia’s Tigers). The entire phenomenon is also sometimes referred to as the African Renaissance.

Figure 3 above shows that before 2000, economic growth rates for Sub-Saharan Africa were largely below the global growth rates but the trend was reversed at the turn of the millennium. Source: World Development Indicators

A look at Sub-Saharan Africa’s GDP performance since 1961 gives further credence to the narrative. As can be observed in the diagram above, Africa has largely out-performed the World since the turn of the millennium. This continuous streak of good performance is unprecedented. Africa is truly rising, and the future seems to beckon. Africa obviously is the world’s next economic frontier: resource-rich and grossly underdeveloped, with one viable way to go – up! As we may agree that Africa is an economic frontier, I ask a frontier for who? Is it a frontier only for drivers of world capital flowing to optimise returns or one for Africans as well?

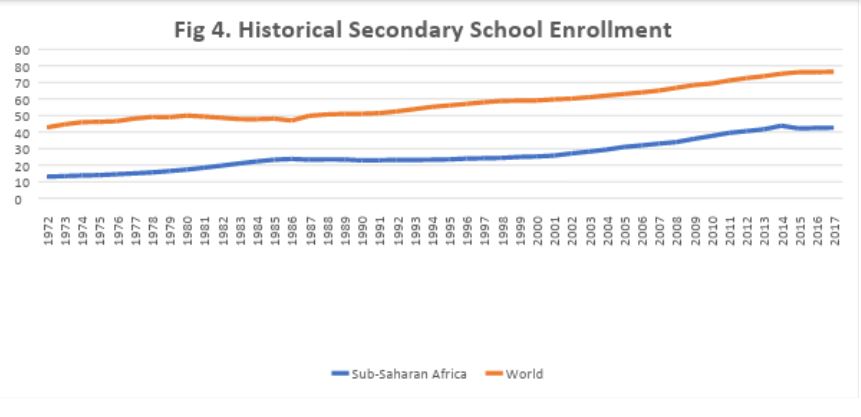

While we so spectacularly out-performed the rest of the world in economic growth, secondary school enrolment variance with the rest of the world is widening.

Figure 4. shows secondary school enrolment for Sub-Saharan Africa compared to the global average.

The quality of education is not positioning our youth and children competitively neither for today nor for the future. Life expectancy is not improving as fast as or has not been commensurate with the growth seen in the last two decades. Inequality is worsening, and youth unemployment is raging. The African Development Bank reports that 70% of Africa’s population is below 30 years and 80% of the workforce is either unemployed or engaged in informal and subsistence activities.

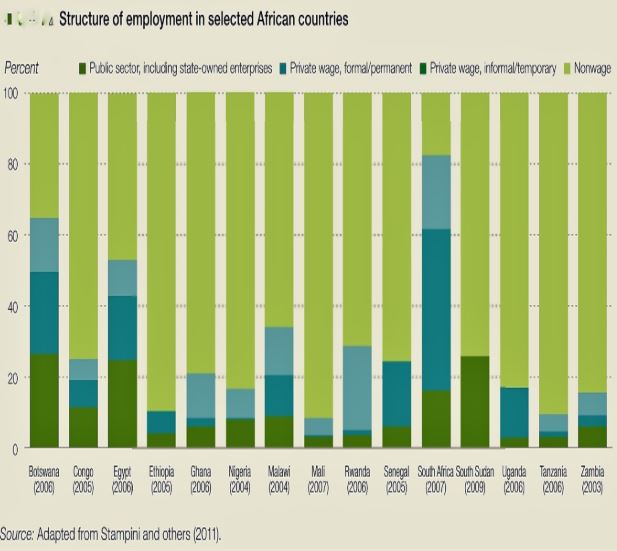

Fig 4. Shows majority of Africa’s labour remains unwaged. This signifies the extent of informal and subsistence activity.

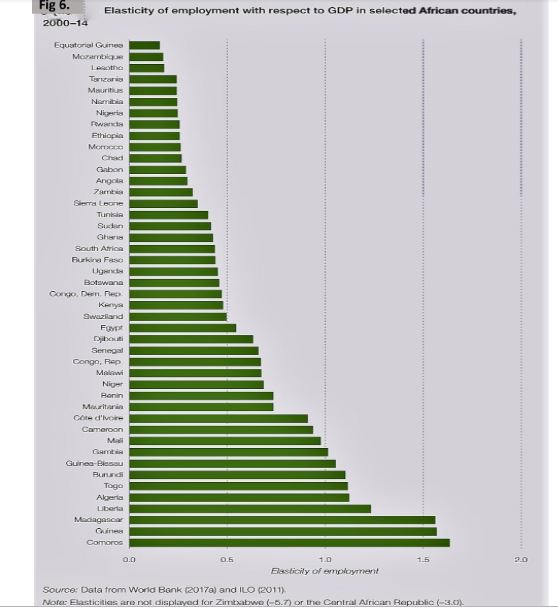

Fig 5. Most Countries are not growing employment commensurate to growth with elasticities below 0.7 which is the South Korean benchmark.

These observations lead me to one conclusion: Africa is rising but not with its own. It is rising geographically but not with its people. Africa is not its geographical location. Africa is its people. Africa cannot rise without its people, else its rise will be unsustainable, and it will only be a rise in absentia.

With 12 million youth joining the African workforce each year, the maintenance of the status quo is a catastrophe in waiting. Social media and the internet have exposed our youth to a definition of a better world and a better lifestyle. They can see the progress and productivity of other youth (in Singapore, Silicon Valley, Zurich and many more). Keeping our youth unproductive, uncompetitive and idle at this scale is dangerous and a time BOMB. It is a recipe for immense social tensions capable of reversing many of the gains we have made in recent decades. Africa’s youth must be put to constructive work. It makes no sense to them that amidst all the resources in Africa, they should be unable to realise their aspirations.

The narrative of an Africa rising without its own must change and the time to change is now.

Changing the Narrative

To change this narrative, Africa must industrialize by optimizing the value of its natural resources and agrarian output. It must structurally transform its economies from a primitive primary production model to a secondary and tertiary production model.

Africa cannot continue to export crude and import petroleum products. It cannot continue to export copper and import electrical cables, export cotton and import used clothing, export coffee and import Starbucks. It is unacceptable that Africa outpaces the world in arable land per capita and yet it is food insecure.

The current primary level-based production economies of Africa make the continent highly vulnerable to commodity price volatilities. While cocoa beans may experience volatility and weakness in prices, the prices of Cadbury and Lindt chocolates are relatively stable. This affirms the economic view that exports of manufactured products are a lot less volatile and sensitive to long term price deterioration. Hence the need for Africa to industrialise. While the cocoa bean may be sold at about $2/kg, Lindt chocolates trade in excess of $20/kg, a whopping 1,000% higher and yet Africa opts to keep thinking at the $2 raw bean level instead of the $20 chocolate value. Sadly, countries like Switzerland with no production of Cocoa are rather known to produce the best chocolates in the world with raw materials from poor farmers in places like Asankragua in Ghana.

In simple terms Africa must industrialize to survive in tomorrow’s world and build a meaningful environment for its growing youth.

In effect the world’s industries will have to expand or relocate closer to raw materials and the growing African demand. As argued by the African Economic Outlook (2018), industrialization is a critical tool in employment generation and poverty reduction and it spurs technological advancement and innovation as well as productivity gains. These are critical competencies required for the survival of any region in today’s and tomorrow’s technological world, a world driven by Artificial Intelligence and critical skills, such as innovation, visionary leadership and effective policy formulation and management.

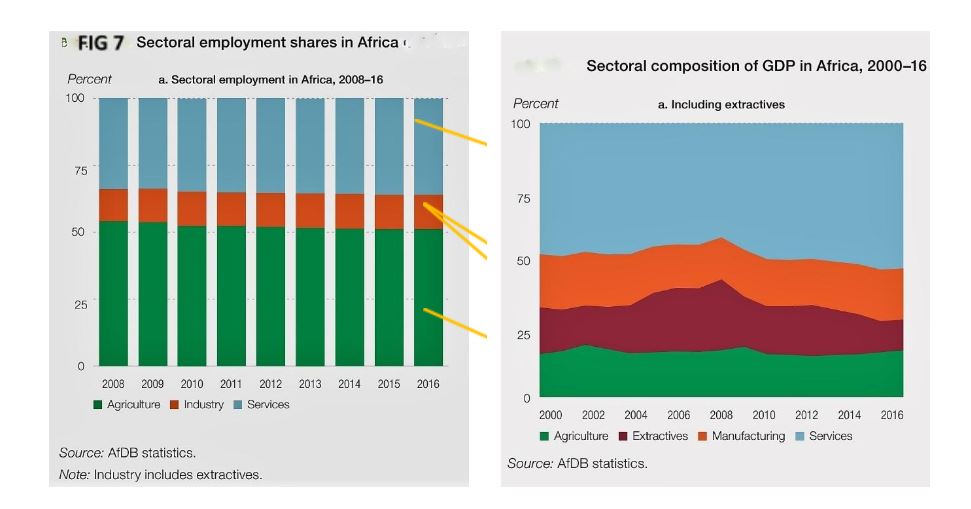

Fig7: Shows the relationship of labour to productivity in the African Economy.

As can be observed in Fig.7, industry that accounts for about 10% of labour and yet contributes about 25% to GDP while Agriculture which contributes about 50% of labour contributes about 15% to Africa’s GDP. Agriculture is key to transforming Africa’s economy but more to the extent that it provides the base for manufacturing or industry.

Compared with other sectors, manufacturing is particularly well suited to create direct and indirect jobs with better pay and working conditions which improves the challenges with inequality and battles poverty. The generation of direct and indirect jobs in manufacturing-related services involves more people in the entire African rising process.

Industrializing Africa will address Africa’s employment concerns and transform its high economic growth rates into increased domestic revenue mobilization for development. Currently, most African countries are performing below the required threshold of 25% of GDP to support infrastructure investment.

Some argue that the rise of African industries will be the fall of developed economies. This view in my opinion is absolutely flawed. The rise of the Asian dragon did not crush the European Union or the North American economies. In any case whose capital will be used to fund Africa’s industrialization? Whose technology will drive industrialization? Whose capital equipment will be imported?

The answer is obvious: the capital, technology and equipment of developed and leading economies to whom increased returns shall accrue.

For the developed world and leading economies, Africa’s industrialization will always be a win-win situation. Hence the call for true economic partnership. Taking a cue from the words of the President of the Republic of Ghana, Nana Akuffo Addo, we call on all to partner Africa build an “Africa beyond Aid”.

To achieve industrialization, policy making must be deliberate and thorough – from the educational and skills development system all through to the realignment of institutions to ensure success.

As argued by a former finance minister of Ghana, Seth Terkper in a recent article, this cannot be achieved without a blueprint and I cannot agree more that Africa’s industrialisation and true transformation cannot be attained by wishful sentiments or the more common ‘live by the day’ firefighting attitude to governance and policymaking but by deliberate actions backed by a clear and committed blueprint. This must be a blue print by Africa, effectively coordinated to harness the varied comparative advantages of its 54 States.

To achieve the desired industrialization of Africa for sustainable development, Africa needs to strengthen its institutions by depoliticising, detribalising and building them on the principles of meritocracy and accountability. This will serve as the bedrock for policy credibility and effectiveness and will require the need to realign politics and Africa’s industry and entrepreneurship.

Politics

Africa’s biggest hindrance to transcending its third world status to first world is the canker of weak policymaking and weak institutions superintended by poor leadership. Combined with a generally passive citizenry and a docile middle-class that believes politics and policymaking are the sole preserves of politicians, a slower reform effort is our lot on the Continent. Africa needs strong and effective institutions to attract the needed capital to spur its industrialization. The current excessive politicization and tribalisation of our institutions have eliminated the culture of meritocracy required for institutional success.

Consequently, the desired investment flow to Africa is hindered by the short-term view investors hold for Africa because of the political risks they perceive from the politicization of our institutions such central banks, regulators, state-owned enterprises etc. These weaknesses translate into the inconsistency and arbitrariness of policy, infringements on the sanctity of contracts and distortion of markets – all superintendent by a corruption-laden bureaucracy. It is no wonder that only one African country – Mauritius – has been ranked in the top 50 most competitive countries in the world out of 137 countries according to the World Economic Forum (2017-2018) and just about Ten in the top 100.

Our openness to do business has also not been any prettier.

Out of 190 countries usually ranked on the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Report, Africa performs sub-optimally. In the 2018 report, Africa has only one nation ranking amongst the top 50 and just seven countries in the top 100.

The eagerness to flaunt political power is an all-too common sight in Africa, which one may refer to as Africa’s Big-manism. This phenomenon is defeatist in the quest for an industrial Africa. As President Obama said, Africa does not need strong men. It needs strong institutions. The worship of politicians must stop and the demand for accountability and true service must rise in Africa, especially from its middle class. Politicians must realise that public service is not a Chiefdom. Electorates do not queue in the scorching sun to vote them into power to be lorded over. The electorate or the citizen risk so much to cast their ballot because they need to be served, their common interests placed above individual, parochial or partisan interests.

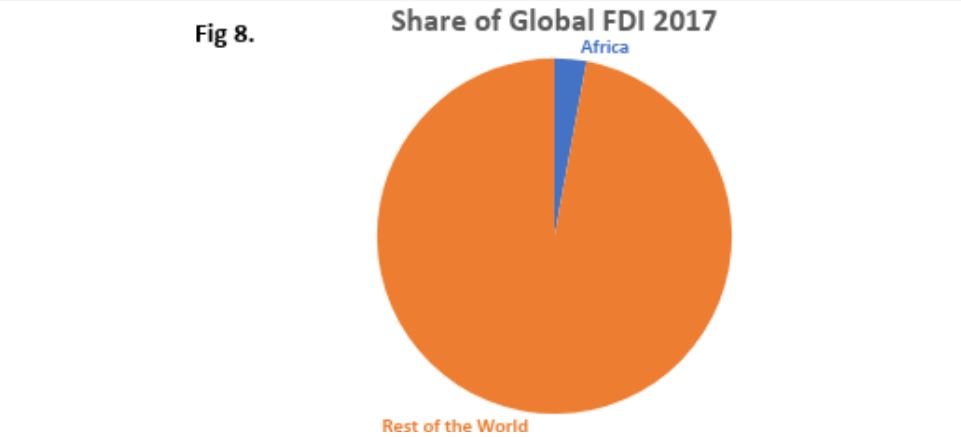

Fig8: Africa’s share of global FDIs stands at 2.9%

The competitive world we are in today has no time for the unprepared. It is the competitive that attract investments. Money is important, but it is also a cowardly bird. It flies only to safer and welcoming environments. The 2018 World Investment Report shows that Africa’s share of Global Foreign Direct Investments stood at a mere 2.9%. To attract money, a country’s policymaking architecture must be trusted, predictable and competitive. It needs meritocratic institutions. For Africa to truly rise with its own, Africa must change NOW!

Industry

The field of Africa’s industrialists and entrepreneurs is awash with so many rent seekers and drivers of political patronage. This excessive dependence on ‘Political Big Men’ who most often than not lose their calling to true service, further weakens our institutions and renders industry significantly passive to policy for fear of vindictiveness. Yet, in developed countries, industry lays the golden eggs that spur economic transformation.

It is important to ask who has the highest stakes in a transformed economy of Africa – Industry or Politics? As industrialists, we invest capital with long-term risks, we hire most of the citizenry and account for most of the taxes. The politician comes and goes. But we, the industrialists, span the lifetime of economies. We have more to lose and must, therefore, begin to lead transformational policymaking and economic management in Africa. We cannot be like the proverbial stomach that takes in anything the mouth throws at it only to warehouse poison someday and die.

Nelson Mandela puts it beautifully when he calls on us to lead from behind. We must lead the policy making space by being very proactive. We need to drive the quality of the process. We must lead in the transformation of our national institutions into competent bodies, independent and devoid of politicking. We must and can change the story of Africa, else Africa’s industry and entrepreneurs will miss the opportunity of leading the continent’s economic transformation, a situation that would mean that Africa will fail to optimise the returns of its own rise.

We must change the way we think and the way we act.

We clamour to be part of the global order in trade and competitiveness. And yet we forget that charity begins at home. According to a report by the World Economic Forum on Africa, intra-regional trade amongst Africans in 2014 was extremely low at 18% compared to 69% in Europe, 52% in Asia and 50% in North America. Yet we believe Africa is rising. This is not only because we may be producing similar goods but that we have erected higher tariff and non-tariff borders even against our less competitive neighbours while adding little or no value to our raw exports. We must evolve our patronage mentality and focus on deepening a competitive value proposition to attract the right partnerships and capital required to transform Africa into an industrialised economy.

In conclusion, I wish to reassert that Africa cannot rise without its own and that the continent must ensure its development is in tandem with the sustainable development and competitiveness of its people, industry and institutions by ensuring inclusive growth. Else, Africa’s rise will be a rise in absentia.

In addition, our economic partnerships must be revised from the extractive mentality to an industrial one where FDIs focus on optimising the value chain from Africa’s enormous natural resources, agrarian output and growing demand.

My former Energy Minister, an Economist, Boakye Agyarko often says, “Every once in a while, the future opens a window to allow the present in”. Africa is rising but its windows to the future will not be open in perpetuity. Africa’s policy and industry must align to make Africa more competitive and attractive in preparedness for its industrialisation. The time to act is NOW.

–

By: Senyo Hosi

About Author

The author is a finance and economic policy analyst with management experience across varying industries including downstream petroleum, public policy management and industry advocacy, finance, logistics, FMCG and commodity trading. He is the CEO of the Ghana Chamber of Bulk Oil Distributors. He is also Managing Director of Legacy Bonds Limited, an SPV owned by the Ghana Association of Bankers and the CBOD and responsible for the administration of over USD500million of Government debt in the petroleum downstream sector. He is a co-architect of Ghana’s Energy Sector Levies Act (ESLA) and the on-going GHs10billion Energy Bond Programme.